Turkish Journalist Visits Armenia to Unravel a Dream

Will Erhan Arik Succeed in Pricking the Conscience of Fellow Turks?

Will Erhan Arik Succeed in Pricking the Conscience of Fellow Turks?

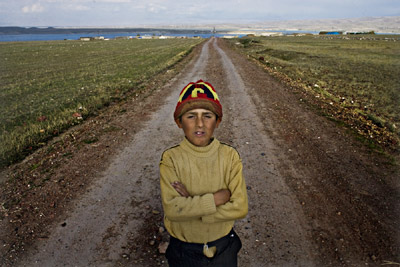

Erhan Arik was born in Ardahan, Turkey, and lived there till he turned thirteen. His ancestors were Meskhetian Turks who hail from the region now known as Samtskhe-Javakheti in southern Georgia. Erhan now lives in Istanbul but visits Ardahan every year. He has many close Armenian friends.

He had heard conflicting reports that Armenians once lived in Ardahan, so he decided to find out for himself. Then he had a dream; a vision that would lead him to Armenia. “I had a dream. I’m in the house in Ardahan where I was born, a house ‘inherited’ from Armenians. And I’m in the part of the house we use as a barn. The voice in my dream is challenging me about this squandered wing of the house: “Why is this room so dirty? Why is this stone hearth where we once cooked our bread now used as part of the barn?” And I woke with a start, haunted by this and many more questions I don't now remember,” Erhan recounts. Erhan decided to visit Armenia to find out the answers to these questions evidently posed by the former owners of the house and to clarify other moot issues in his mind.

“We have been fed a national interpretation of history”

“Until now, we Turks have learnt everything we know about Anatolia from ‘official sources’, from an ‘official’ version of history churned out by these same sources, as categorical in tone as it is consciously nationalistic. We were fed this nationalist interpretation for years,” said Erhan. He noted that certain episodes of history, particularly the events of 1915, create complications for young Turks and Armenians. “Regardless of the fact that one is fed propaganda as a young pupil in school, you reach an age when you want to fill in the details.” In Erhan’s view, Armenian children, from a young age, are brought up on a diet of violent war tales and that the kids are told these stories by their elders before going to bed. It cultivates an atmosphere of fear and dread in them, he argues. Erhan Arik graduated the media studies department at Anadolu University and for the past five years has been working as a documentary photographer and videographer, focusing on social issues. For the last three years he has been closely involved with internet broadcaster DEVİNİM TV as both project coordinator and director in Turkey. He’s now busy with multimedia reportage.

Multimedia coverage from both sides of border

“Anadolu Kultur” is the Turkish organization that has financed the project that has brought Erhan to Armenia. He plans to travel to the border villages and use multimedia resources to record tales and stories from the area. Before coming to Armenia, Erhan had visited border villages on the Turkish side.

He notes that the same “horovel” peasant melodies are sung on both sides of the border. “In Anatolia, the horovel is the song that helps prepare the peasants for their work, while gathering and mobilizing the necessary internal and external strength needed to complete the work. This song is called as horovel on both side of the border. The same melody is also sung in Armenia,” Erhan says. He also says that they use many words in their everyday speech which are holdovers from the Armenians. For example, the Turks use the word “agos” (furrow) with the same meaning that Armenians do. “There are no longer Armenians in Ardahan, but the culture remains,” says Erhan, noting that the two peoples on the border need to recognize the existence of the other and get better informed.

Armenian barber tells him to speak in Turkish

Erhan recounts that when he was recently in Armenia he went to a barber shop and was speaking English to the barber who asked the translator why Erhan wasn’t speaking to him in Turkish since he knew more Turkish than English. For example why was Erhan using the word OK instead of “tamam”, which the barber explained was more his style.

The Turkish photographer says that he approaches the Turkish-Armenian issue with sensitivity and that he participates in the discussions in various internet forums. He says that people in Turkey have been fed misinformation on the issue since the beginning and that he has come to Armenia to recollect the past and then go back and tell his countrymen. When I asked Erhan what had changed since coming to Armenia, the journalist said, “More or less I now know what they did to Armenian. Before visiting Armenia I knew that more than 2 million had been exiled and nearly 1 million lost their lifes. That fear of being a minority, of living a cowered existence, is still felt by those few Armenians who remain. I even see it when I go to the offices of “Agos”. You see the people working behind those heavy iron doors. They feel safe like that and I want to ask them the reason.”

While in Armenia, Erhan has visited the border villages of Margara, Pshatavan, Bagara and Yervandashat. He’s also traveled to Gyumri. But there are a few more villages on his list to go to. He says that his research isn’t restricted to the villages and that he converses with average townsfolk as well. “When I’m sitting face to face with a survivor of 1915 events for an interview, it’s a very moving experience for me. They look into my eyes and say that their parents, brothers and sisters were murdered,” Erhan said.

I asked him if he’d be able to return to Turkey and convey what he heard and found out here in Armenia and to state categorically that the Turks actually committed a genocide. Erhan avoided a straight answer. “Being on the side of the Armenians is very problematic. What’s most important is how people express themselves. I say that I’m on the side of reality rather than simply the Armenian side.” Over on the Turkish side of the border, Erhan has also travelled to Azeri and Kurdish villages.

Kurds want border to open, but not Azeris

He says that from what he heard and saw, the Kurds want the border to open and for Turkish-Armenian relations to improve. On the other hand, Azeri villagers are against any relations with Yerevan and regard Armenians as their mortal enemy. Erhan believes that the unwritten Turkish precondition of a Karabakh settle for normalization of Turkish-Armenian relations will gradually be separated out of the process and that the day will come when Turkey will draw a clear distinction between the two issues.

The journalist believes that the role of Russia in the Karabakh issue is paramount and that if Russia were to say that the border should be opened without any Karabakh settlement, it will be. Erhan believes that Turkey will sign the Protocols before April 24th and that Armenia will soon follow.

Turkey must free itself from Armenian ‘hang-up”

The journalist believes that the opening of the border has strategic and economic significance in the Trans-Caucasus for the two governments. He says that Turkey will finally be able to free itself of the “hang-ups” in has towards Armenians. “The border opening is necessary to restore memories that have been quashed for 100 years. That’s to say what the Turks have forgotten,” explains Erhan.

His multimedia work, based on his research conducted her in Armenia, will pose some of the following questions as well – Where are more than one million Armenians; where are the more than two million deported Armenians? “I have long ago found the answers to these questions,” Erhan says. Through the experiences of a Genocide survivor, Erhan has to attempt to explain to his countrymen what their forbearers have done. “If I can reach their conscience, then something just might change,” he says.

Photos: Erhan Arik

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment