Sweden Revokes Armenian Doctor’s Medical License: He’s Now Practicing in Cyprus

Doctors who have been stripped of their medical licenses due to serious violations can easily move to other countries and continue to practice medicine.

This is possible due to ineffective warning systems, indifference, and lack of accountability from state authorities.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) recently conducted an investigation spanning Europe and beyond revealing how doctors who have been banned for major wrongdoing, including causing psychological and physical damage to their patients, relocate and pick up their careers.

Reporters across fifty media outlets, including Hetq, worked for months to trace banned doctors who are still licensed and practicing in a different country and asked the question: How?

The investigation, entitled Bad Practice, identified more than one hundred doctors who were stripped of their licenses but were working in other countries.

We did not find such stories in Armenia, as there is still no individual licensing of doctors, and there is also not enough public data to conduct such research. That is why we started searching for Armenian doctors in foreign databases available to us.

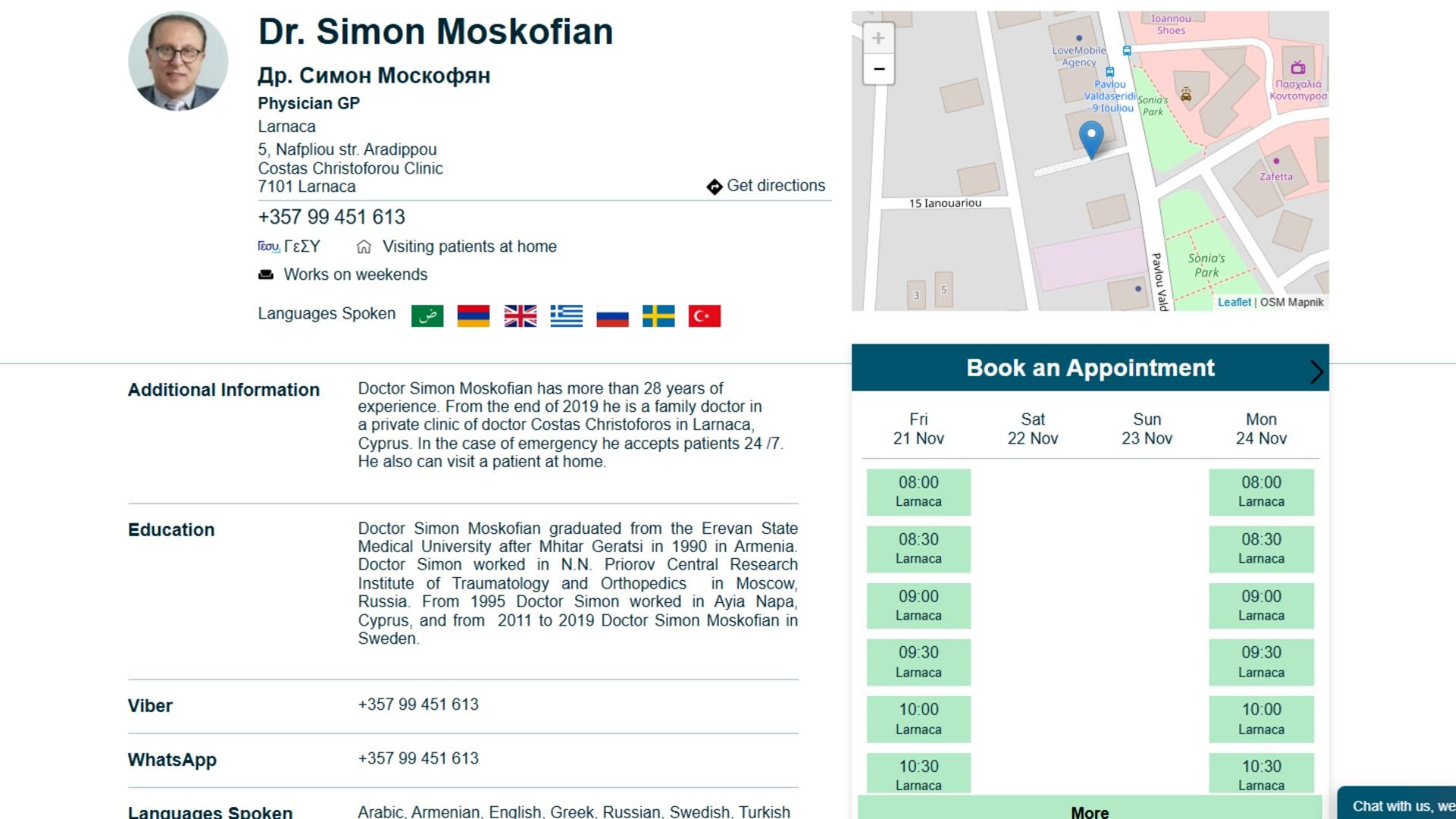

One such story is about Simon Moskofian, a therapist who worked in Sweden.

The Swedish Health and Welfare Inspectorate completed an investigation into Simon Moskofian’s professional activities at a health center in southwestern Sweden in December 2021. Their conclusions were harsh: the therapist lacked fundamental knowledge in several key areas of medicine, failed to conduct sufficient medical examinations, and deliberately or negligently violated regulations that were essential for the safety of patients.

Hetq and the Cyprus Investigative Reporting Network (CIReN) have examined the Swedish documents of Moskofian’s case histories, which describe in detail how he made inappropriate appointments and performed deliberate or negligent actions during the treatment of fourteen patients, which caused complications, and in one case, death.

We have singled out the following three cases.

Case 1

In September 2018, a 72-year-old patient went to a private clinic to receive a steroid injection to relieve shoulder pain. A few hours after the injection, the patient had difficulty breathing and called an ambulance. A bilateral pneumothorax was found in the hospital (pulmonary rupture - ed.), and thoracic drains were inserted.

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (SNBHW) writes: “The medical record lacks information on the injection site, drug, and dosage.”

The (SNBHW) concluded that the doctor (i.e., Moskofian) did not ensure the necessary level of safety during the treatment.

Case 2

On August 2, 2018, Dr. Moskofian and a nurse visited the home of a patient born in 1930. The medical record states that the patient had prostate cancer and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), his breathing was shallow, his frequency was 48–50, and he did not respond to conversation.

The medical record states that antibiotics were prescribed via intramuscular injection. The same document is also attached to the death certificate, but there is no mention in the medical evaluation that the patient died on the same day of the visit.

The SNBHW notes: “The record does not indicate that the issue of changing the treatment goals or planning for palliative care was discussed.”

The SNBHW concluded that the treatment and documentation did not meet the requirements.

Case 3

On June 26, 2018, Dr. Moskofian and a nurse made a home visit to a patient born in 1954. The record states a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, but there was no anamnesis (the process of a patient recounting their medical history to a healthcare provider) or physical examination. Medication decisions were made by telephone consultation with the psychiatrist on duty.

In July and August, Moskofian referred the patient to the psychiatric department without conducting any examination himself.

In September, a new referral was made to the hospital’s emergency department with the note: “Intestinal bleeding. Blood transfusion.” The record does not contain any information about the patient’s condition, blood tests, or hemoglobin.

The SNBHW records: “It is impossible to understand what happened to the patient.”

Its conclusion states that the patient’s treatment and documentation did not meet professional requirements.

The SNBHW, after reviewing these fourteen patient files, concluded that Simon Moskofian did not comply with professional requirements and revoked his medical license.

License Revoked, Dr. Moskofian Sets Up Shop in Cyprus

Following the notice of license revocation in Sweden, Norway also revoked Moskofian’s medical license in early 2022, but he still has an active medical license in Cyprus and is registered with the country’s national healthcare system (GeSY), working in one of the clinics in Larnaca.

Moskofian told the Cyprus Investigative Reporting Network (CIReN) that he returned to Cyprus and started working in late 2019 “at the encouragement of his doctor friends,” and not because of the investigation launched against him in Sweden. His family cited another reason for his return; that he has lived in Cyprus since the age of thirteen, in 1972, when he moved from Lebanon. Moskofian received his medical education at Yerevan’s Mkhitar Heratsi Medical University. Moskofian told our Cypriot colleagues that he also studied in Moscow.

The doctor claims that despite the seven years he spent in Sweden being “extremely overworked and tired,” he would not have worked for so long if he had not been able to. He says that before leaving Sweden, he met with the licensing authorities, who “assured him that his license would not be revoked.” Moskofian claims the licensing authorities later “behaved dishonestly and did not live up to their promises.”

Hetq contacted Yerevan’s State Medical University to find out what Moskofian specialized in when studying there. The university refused to provide any information, citing the Law on Personal Data Protection.

We also tried to find out whether he sees patients travelling to Cyprus from Armenia, but came up empty-handed.

The OCCRP investigation revealed three systemic problems in the medical licensing systems it studied.

1 - Many doctors who have their licenses revoked for serious misconduct or harm to patients easily continue to practice in another country.

2 - Doctors’ disciplinary histories are rarely made public, creating a climate of ignorance and vulnerability.

3 - Information sharing between licensing authorities in Europe is patchy. Notices of license revocation in one country do not always affect a doctor’s ability to continue practicing in other countries.

The European Commission’s Internal Market Information System is designed to inform the thirty member states about disciplinary actions. Hetq and the Cypriot CIReN obtained anonymous notifications sent on the days of Moskofian’s Swedish and Norwegian licenses being revoked. Since Cyprus is also a member state, it should have access to this information.

The Cyprus Medical Council, however, did not confirm whether it had received the 2021-2022 notifications, but in response to a request from CIReN, it stated that it “has already launched an investigation and will take all necessary measures.”

At the time of publication, Dr. Moskofian was still offering patient consultations in Cyprus.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment